We’re Killing the Love of Reading, but Here's an Easy Fix

(Prefer to listen? Click here for the TQE Method on the Cult of Pedagogy podcast and TQE at the top of this site for the UnlimitedTeacher.com TQE Page!)

Students and teachers are frustrated. There's a good reason and luckily, a simple solution.

Teachers want students to master reading skills, to love reading, to, please, just read.

Students want to complete the question list.

This past fall, my students shared their experience of studying novels before they came to my 9th grade Honors ELA class. Read this book and answer these questions.

The record? 141 questions, and according to the students, almost exclusively plot-based to check reading completion. Not understanding. Not author’s purpose. Not thematic relevance. Completion.

(Please know I do try to take complaints with an entire shaker of salt, but... they gave me the worksheet. No, list. Same thing. 141 questions.)

In our class, they got to experience a more collegiate style of discussion and though it took some time to get accustomed to the procedure and the goals, they were soon experts in reading the text, analyzing author’s purpose, and preparing impressive class discussions, all by their 14- and 15-year-old-selves.

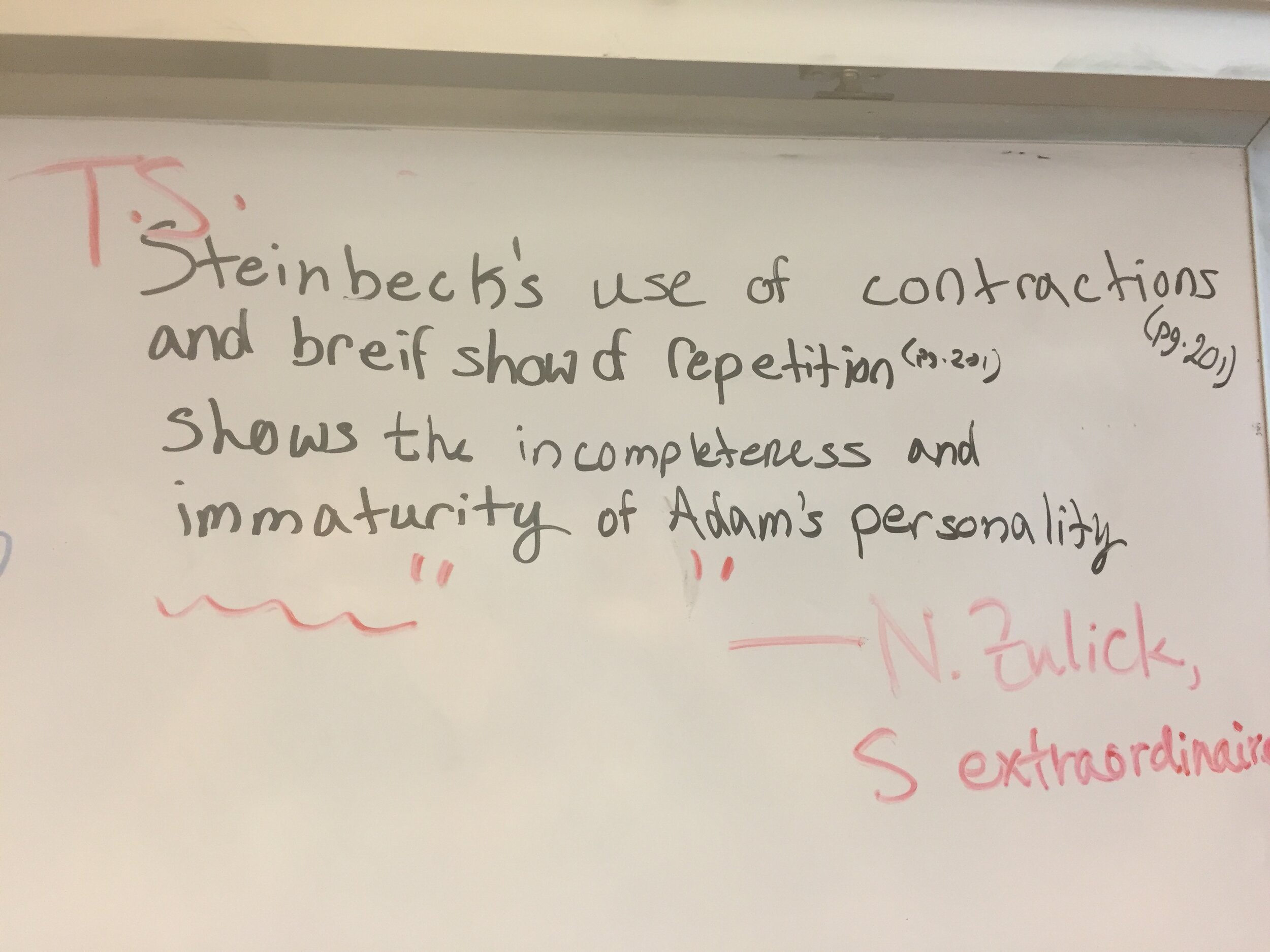

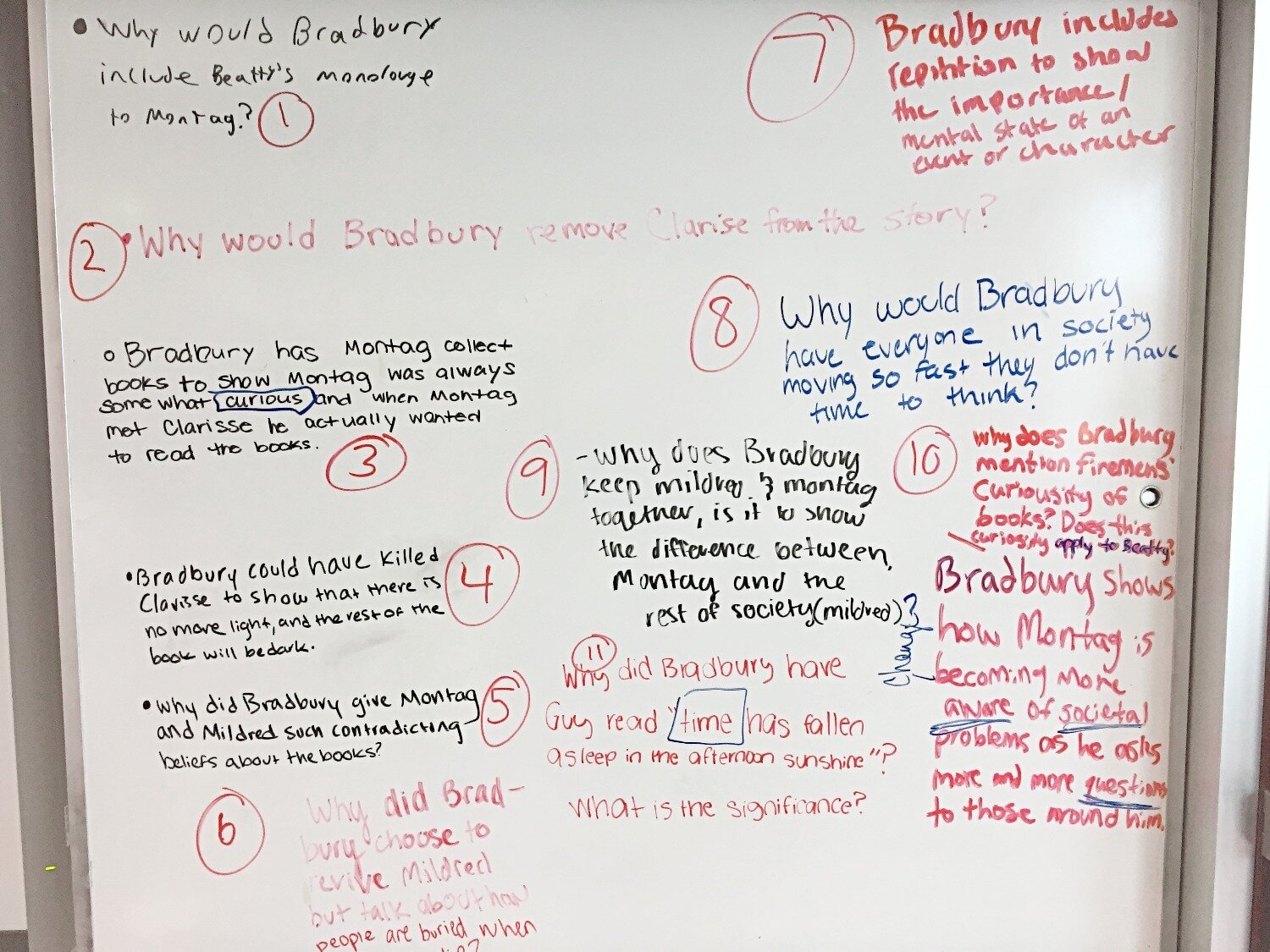

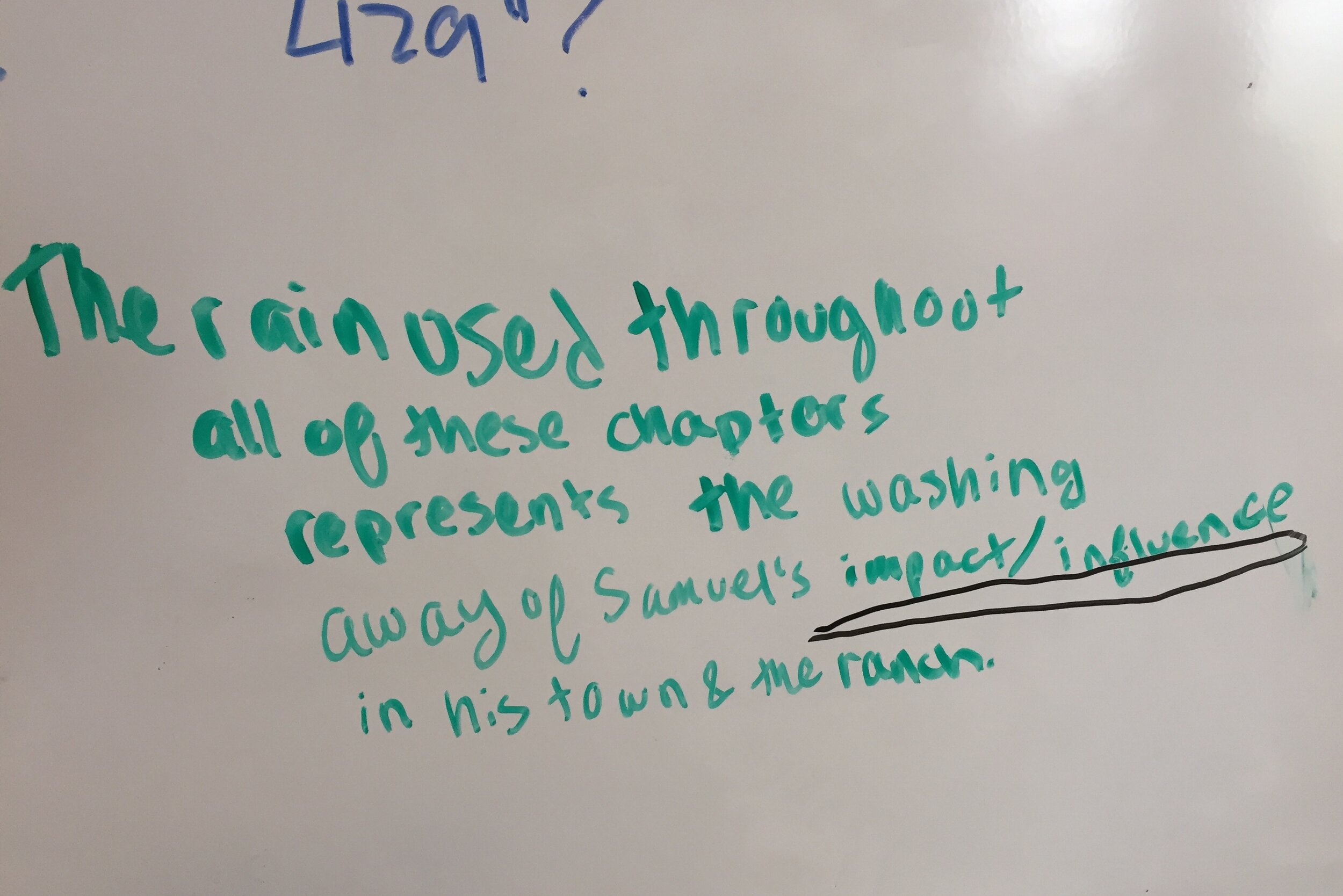

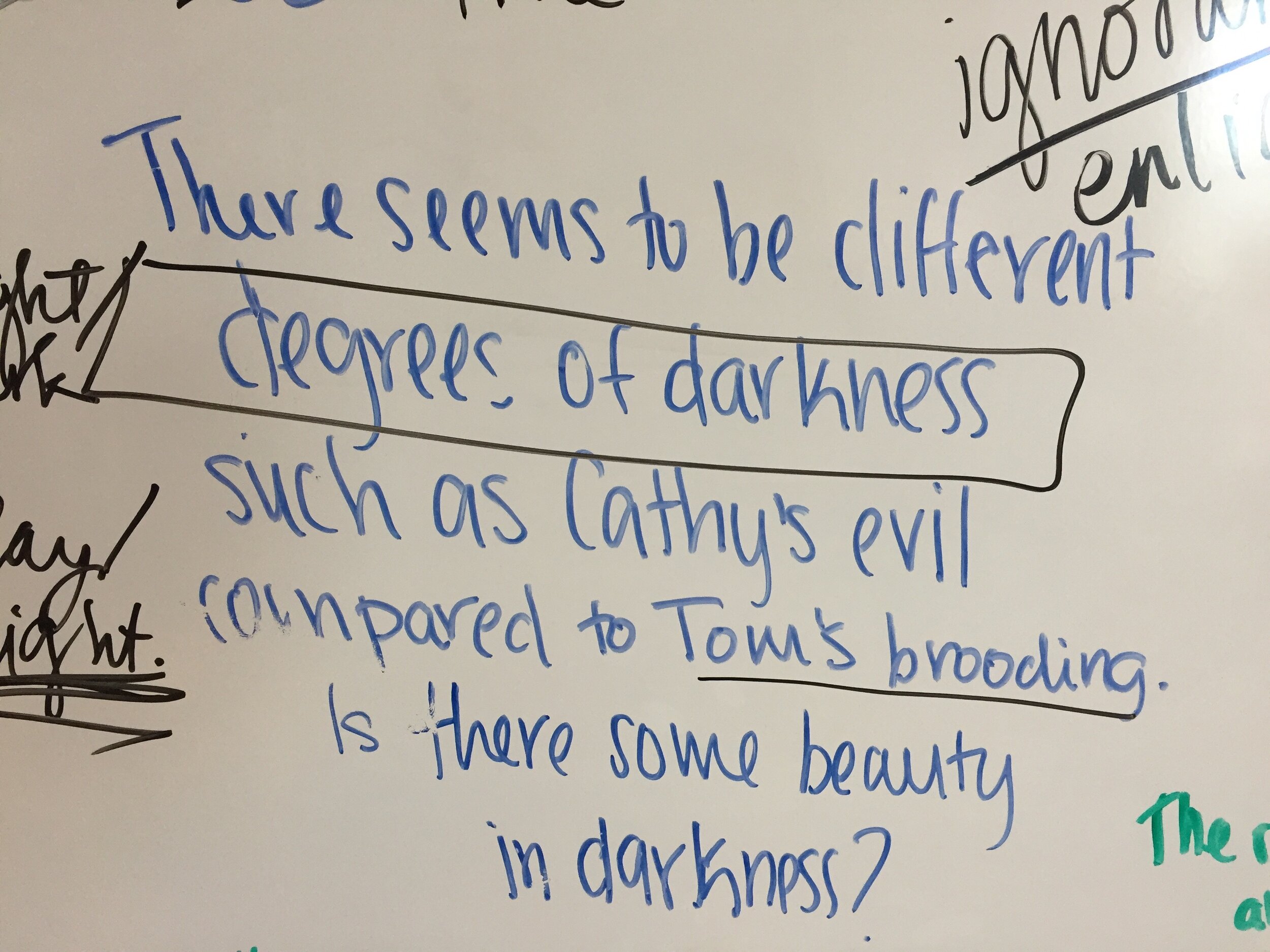

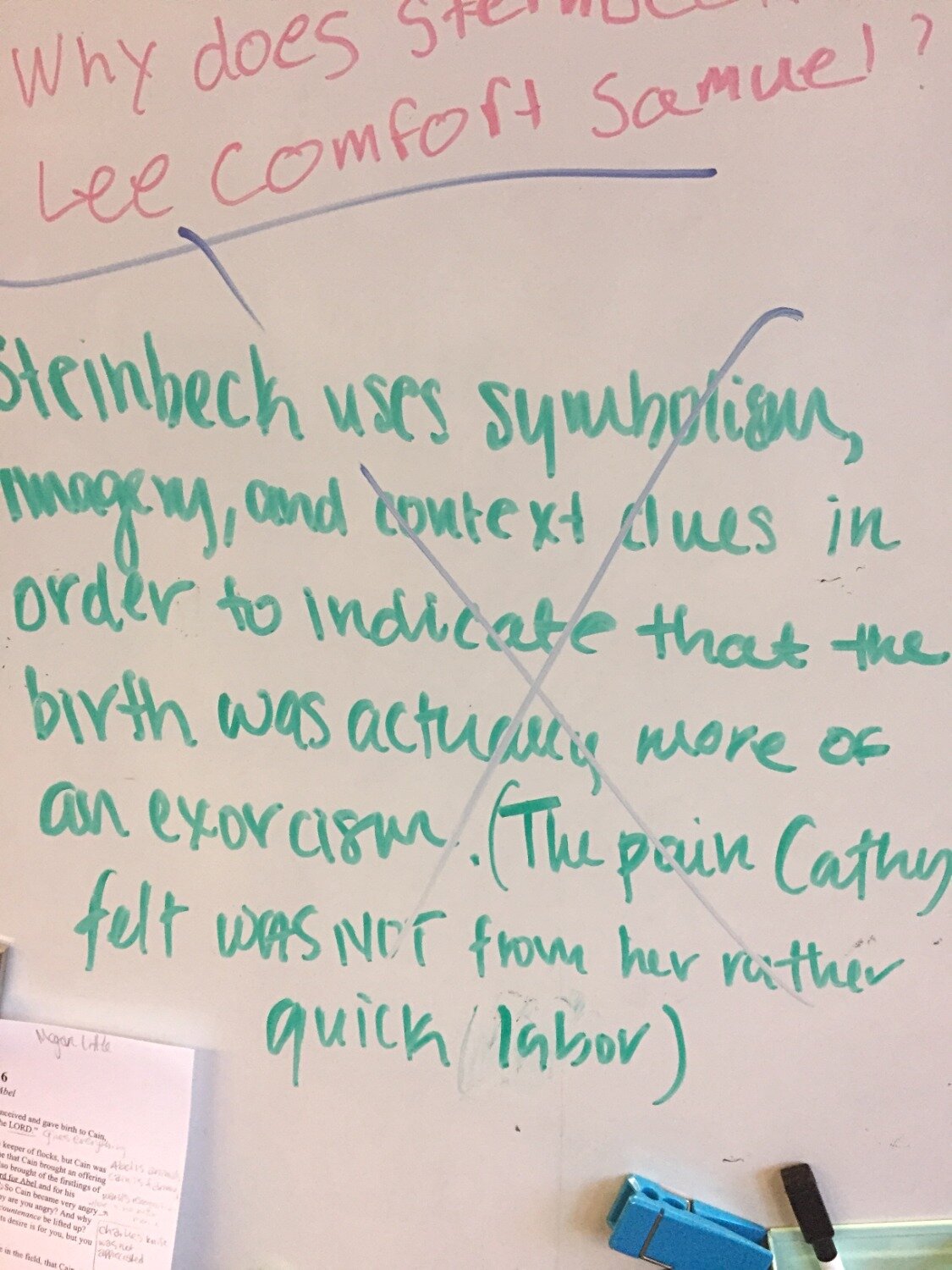

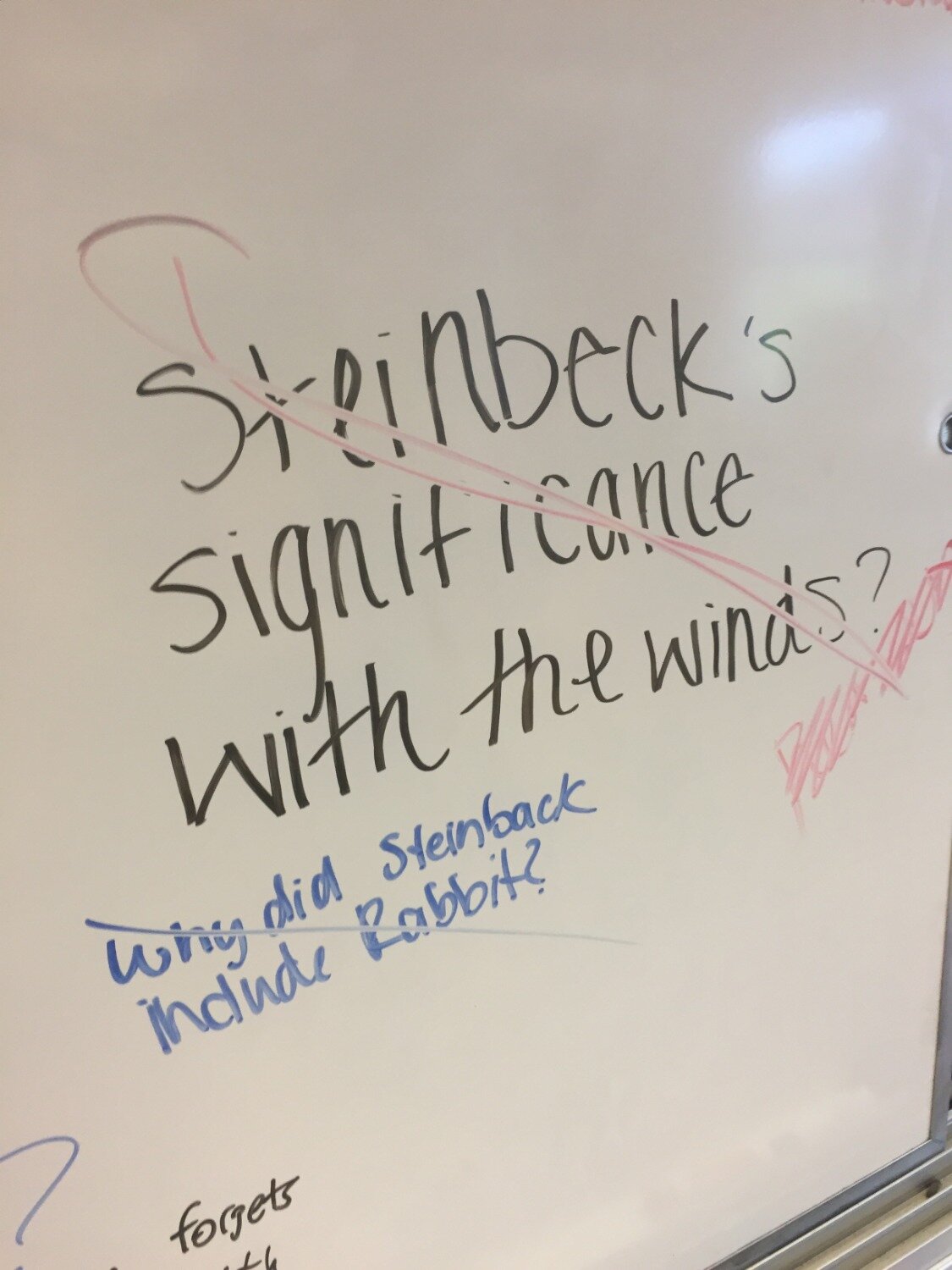

Some of their beautiful “thoughts, lingering questions, and epiphanies” (please excuse the shorthand):

So how did we get here? How did we come to the point that one student said she “[felt] like a literary detective” and another stated it was like we “get under the skin of the book?” Hint: It wasn't with a list of questions.

Like many new teachers, when I first started teaching a dozen years ago, I used colleagues’ questions or questions found online. Students copied answers from classmates, from websites, from wherever they could find them. I filled out referrals and had students call home; nothing motivates students to love reading like referrals and restrictions. Some read until they found the answers then abandoned the book. Others diligently read and answered, but they still felt as though they didn’t know what they were reading about or why.

To combat the problem, I stopped with other people’s questions and created my own, decreasing the question quantity to no more than four per reading assignment, increasing the quality to require higher-level thinking, but still the response was the same:

I answered your questions. Where’s my A?

Yes, but what did you think?

My questions were the problem. And not the questions themselves, as they were of the highest levels of Bloom's/Depth of Knowledge levels, but the fact they were mine. They were what I discovered, what I focused on, what seemed relevant to me. I succeeded in showing students what I connected to from the reading, but they were not practicing these skills; I was. And as we know, when the teacher is doing the thinking and the creating, then the teacher is the one doing the learning. Not the students.

An Easy Change

A few years ago, I was inspired by Grant Wiggin’s article, A veteran teacher turned coach shadows 2 students for 2 days – a sobering lesson learned, and decided to adapt the beginning-of-class discussions to my content and my reading goals: getting students to understand an author does indeed have a purpose and making sure students can analyze what writing choices help the author communicate this purpose.

For the last novel of the 16-17 school year, I announced to my junior ELA course there would be no reading quizzes, no assigned questions, and no test. Your reading comprehension assessment will be discussion-based and this can mean either asking questions or answering them, as long as what you say proves you understand the novel. If you do not like your score, you can provide your annotations and/or take a test when we’re done to get a higher score. I wish you could have been there to see their skepticism.

We had six student-only class discussions for The Things They Carried and I listened in proudly as new leaders emerged. The questions and discussions improved with practice, but even the least impressive class periods were still better than what we had been doing, because I had proof the students were doing the collaborating, the analyzing, the thinking. They loved the book, as expected (it is a favorite). They knew they could succeed if they simply read and discussed with their classmates, and since they didn’t have to enter class feeling bad about not having their questions done, they were more apt to participate and therefore more apt to read. It worked. The best moment was when several students, even some who had failed English every semester of high school, said they felt smart.

I reflected, adjusted, and applied this approach to my honors courses for the entire 17-18 school year. After comparing the topics we thoroughly discussed during our study of the novel, my students had missed only seven of my own years-ago-assigned novel questions for To Kill a Mockingbird. Only seven. (Full disclosure: Ok, I did provide these seven topics, per the students’ request. So, technically, I did "assign" some last year.)

Once students master this process, it feels like I'm back in my literature courses from college. Students say they wish they could go back and read those books to find out what they’re really about; I promise them the books still exist, they have time, and probably will read many of them again. As with any great movie, every time you read a great novel, you’ll find something new, especially since you now know how to find it.

At the end of the year, students completed course reflections and surveys. This TQE process was the top voted "You Have to Keep This" item for reading.

The TQE Process:

Students read the assigned reading at home and hopefully, some annotations their way (for a great annotation scaffold, see my post "Annotate My Way, or Else."); if not, they read in the hall during small group discussion to catch up and return to class for the class discussion when they finish (I haven’t found a great solution to this, but students soon found they understood the novel better when they read at home and were part of our class discussions)

Small Group Discussions as students entered the room

I do project question stems, but after one novel, students don't need them, only the reminder to use the author's name as often as possible (quite a shift for them)

At first, students are most comfortable using the more simplistic question stem on the left because they mimic their familiar pervious reading assignments, but I model the questions on the right side during the first class discussions

Top 2 Thoughts, Lingering Questions, or Epiphanies (TQEs) on the board by the end of 15 minutes

Class Discussion of TQEs

This slide is available for free; click here!

Tips:

"Good" TQEs typically include the author’s name

Lingering Questions should not be plot-based

If possible, groups should also provide their best guess for any question

Groups should expect follow-up questions about whatever they write on the board

Students should record their own TQEs from the Small Group Discussions in one ink color and the Class Discussion in another, all on the same page

Bored with the routine?:

Assign the TQEs a number and give them to different groups for a response

Have a student volunteer to lead the discussion

Class votes on top TQEs and focus only on those

TQEs become thesis statements and students complete an outline

Can this work remotely? Yes. Click for the templates.

So you know… The Ultimate TQE Course launches in just a couple weeks! In it, I’ll share how TQE can be the foundation for everything meaningful, fun, and efficient — and I mean everything: reading, writing, inquiry, discussion, collbaoration, feedback, creating, exploring, everything.

I’m SO excited to share all of it with all of you! Click here and you’ll get the information first.